All the time in the world

There are two clocks on the wall of the dimly lit hospice room. Neither of them shows the correct time. There are two beds, but only one is occupied. My grandpa looks old but also child-like, lying there with oxygen cannula in his nose and a blanket tucked under his chin. His wife feeds him bits of tuna sandwich. It’s almost a hundred degrees outside, and the portable air conditioning unit attached to the window cools the room, but it’s loud, and combined with the oxygen machine, with its constant humming, I can hardly hear my grandpa’s words. That is, when he’s lucid enough to speak at all.

I haven’t been to see my grandpa in several years, perhaps since my son was a baby but probably before even that. He stopped traveling years ago because of his health, and it became easier and easier to avoid the three hour car ride to see him since his taciturnity was off-putting and life got busy. But seeing him now, his mind and body failing him, I am filled with regret. In snippets of conversation with his wife—who is not my biological grandma but who has been married to him since well before I was born—I learn things I didn’t know, and I start to get a picture of this frail man in the bed, a picture I wish I had glimpsed a long time ago.

I rode down here with my dad. It’s his second trip in a week to visit his father, not knowing whether this time will be the last. In the car we talk about things that we’ve avoided for years, the proverbial elephant in the room of our relationship, namely my parents’ divorce. I’d never heard his side of the story in 11 years, and I’d been holding onto anger that whole time. We’re honest with each other for the first time maybe ever, and a door is opened to authenticity, a door I had been afraid to open for far too long. I wish it hadn’t taken my grandpa’s imminent death to reconcile me to my dad, but I’ll take what I can get.

I ask my dad if there’s anything he wishes he’d said to his dad before his mind started to go, before he found himself in a hospice bed with his kidneys failing. He says he feels like he’s at peace with their relationship, though perhaps he wishes they’d been closer all along. I’m hopeful now that, with the years left with my dad, we’ll continue to find out new things about each other and build our relationship. I’m glad I didn’t wait until it was too late.

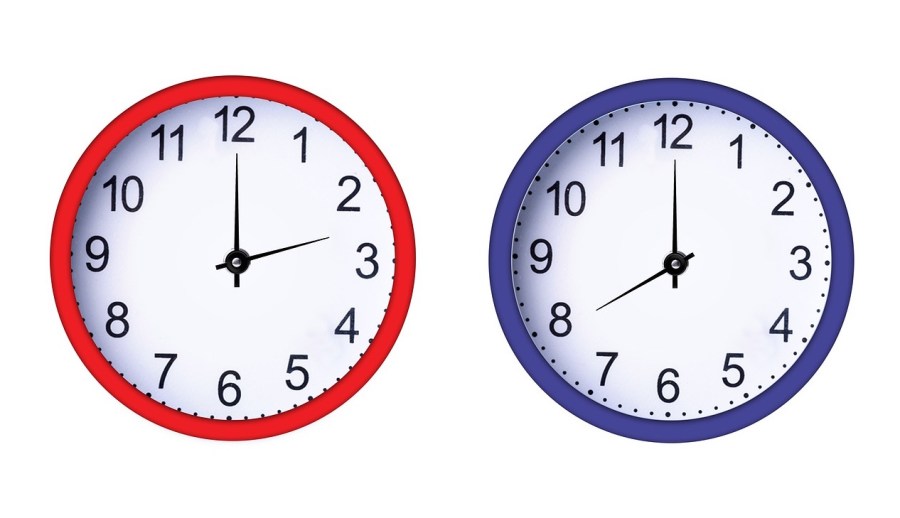

Just before we leave my grandpa’s bedside to head back home, I adjust the time on both clocks so they are correct and in sync. It feels symbolic, like a reset of the time I get to spend with my dad now. Someday I may be sitting by his bedside feeding him bits of tuna sandwich or sleeping in a chair holding his hand through the night. There will come a time when I don’t know which goodbye will be the last. But for now, it feels like we have all the time in the world.

Rachel Womelsduff Gough and her family ditched the city for a patch of earth in the Snoqualmie Valley. Cheered on by her husband and two blonde babes, Rachel learns by getting her hands dirty, whether it’s gardening, chicken farming, neighboring, or adventuring with soulmates in wild places. She is a Mas ter of Divinity student at Fuller Theological Seminary, and she can’t live without books, coffee, and mountains.

ter of Divinity student at Fuller Theological Seminary, and she can’t live without books, coffee, and mountains.

Beautiful

LikeLike

Beautifully written Rachel. Wow!

LikeLiked by 1 person